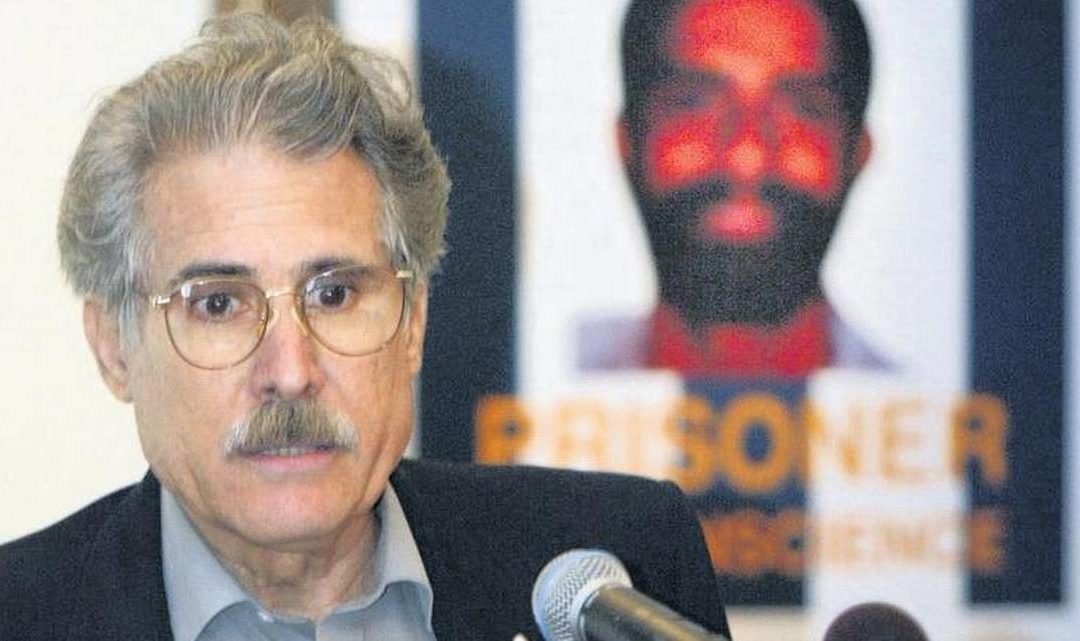

PHOTO: ARCHIVO/EL NUEVO HERALD

On July 12, 2019, almost forgotten and as poor as he lived in Cuba, Ricardo Bofill Pagés passed away in his modest Little Havana home.

Like walking through a minefield, right in the middle of a totalitarian, intolerant system, Bofill and a group of friends founded the Cuban Committee for Human Rights (CCPDH) in Havana in 1976. Over the years the organization strengthened, marked historical milestones and multiplied to become Cuba’s current human rights and peaceful opposition movement.

Bofill’s endeavour in Cuba, entering and leaving prison once and again without giving up his ideals, confirms that individuals, contrary to what ordinary Marxism says, do play a key role in History.

This unrestful, visionary man understood that human rights violations in his country were not occasional, but intrinsic to the legal bodies. He also concluded that after Fidel Castro’s regime drowned in blood the clandestine armed struggle, the only feasible way of fighting totalitarianism was to do it peacefully, in the open and based on the UN-promoted platform of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

He worked tirelessly while living in Cuba, distributing at his own risk typed and carbon-copied denouncements to foreign press agencies and embassies. In 1987-88 with a dozen colleagues who had joined him in prison or out in the streets, he carried on a series of initiatives that essayist and CCPDH member Ariel Hidalgo has called “Cuba’s first dissident offensive”.

These included requesting a Catholic mass in a church at El Vedado neighborhood in memory of the murdered Polish priest Jerzy Popieluzko. After the ceremony he unveiled a strong critical document entitled “Havana appeal” which only a handful of the attendees signed. He went on weeks later to call and record a roundtable in which participants exposed different aspects of the human rights situation in Cuba. The event was later on broadcast back to the island by Radio Martí; and finally, he supported a dissident art exhibition in the very heart of Vedado that was assaulted by government mobs. Meanwhile, a number of workshops and interviews with visiting representatives of Amnesty International, Americas Watch, and other international organizations and media were conducted.

The government reacted by trying to discredit Bofill on its media, yet they only got the Cubans to know him better, and for the CCPDH to grow. Bofill’s speaking out from Cuba, presented in Geneva by U.S. ambassador Armando Valladares before the 1988 annual session of the UN Human Rights Commission, resulted in a compromised situation for the Castro Government. So Castro’s representatives were ordered to invite a working group from the Commission to visit the island, which took place in October. Bofill was prevented from giving his personal testimony to the working group, but up to 89 of his peers did. The delegation left Cuba and, in February 1989, issued a report containing 400 pages of complaints about human rights abuses.

This was the preamble for the Genevan forum to appoint in 1991 a Special Rapporteur for Cuba, a procedure that is only implemented for critical human rights country situations. Even though he never got permission to visit the island, the Rapporteur remained active and issuing annual reports until Pope John Paul II’s visit to Cuba in 1998. Nonetheless, international scrutiny on the situation of essential rights in Cuba continues, based on what Bofill’s successors report from Cuba.

Among his virtues as leader Ricardo Bofill distinguished himself by knowing how to listen and embrace the initiatives of others. Also for his tenacity. It is said that once while he was imprisoned at Combinado del Este, a state security officer told him, “Bofill, stop sending ‘balitas’, we caught those two you sent.” “Balitas” are clandestine messages handwritten in tiny letter that the inmates compress and seal with nylon to get them out of prison. Bofill replied, “Ah, you caught two balitas ….? Then the other three went through….!!

He had the vision and courage to understand that, as much as the Castro regime demonized them, the United States and the Cuban exile community were the only consistent allies that dissidents and opponents on the island could count on. And he also had the clarity to send his denunciations to Radio Martí ─the U.S. government broadcaster for Cuba founded at the behest of the great exiled leader Jorge Más Canosa─ as the only way for Cubans on the island to learn what the CCPDH was doing next door.

On one occasion Bofill said that the history of the fight against totalitarianism in Cuba could be divided into before and after Radio Martí. The same could be said of him, as a watershed divider of Cuba’s recent history: before and after Ricardo Bofill.

But the best tribute to the life that recently extinguished in Little Havana is still paid by Cubans on the island who, when the authorities, as usual, procrastinate the solution of a critical problem, they promise to take it to those whom to this day they call ─no matter if they are activists, political opponents, alternative journalists or members of the independent civil society – “those human rights guys.”