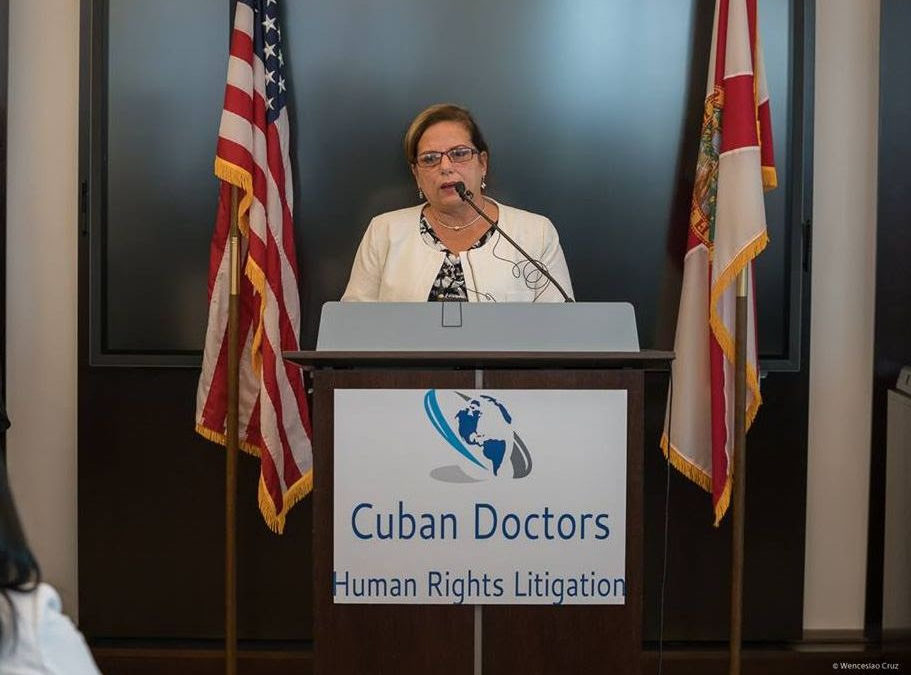

On Friday, November 30, an initial group of four Cuban doctors, three of them women, initiated a collective legal process (class action) for damages against the Pan American Health Organization for its complicity with the governments of Brazil and Cuba in the engineering and execution of a modern slavery scheme of Cuban doctors. PAHO benefited by an estimated amount of about 75 million dollars extracted from the wages earned by the Cuban doctors while handing over to the island’s government, through a front company of that totalitarian regime, between 70 and 85 percent of the total that they had earned with their work.

The group of plaintiffs may add others who wish to do so in the coming weeks. (Visit the site)

Cuban independent historian Dimas Castellanos, in an article published by Diario de Cuba (DDC), November 27, presented eight excellent questions and four conclusions on what happened with the Mais Medicos program that we have chose to reproduce here:

1- The revalidation of doctors’ medical credentials is a practice in place in many countries. If Cuba believes that Brazil’s intention was to question Cuban doctors’ qualifications, why not, instead of withdrawing them, seize the opportunity to demonstrate their capacities to the world?

2- If Cuban doctors are fully identified with “revolutionary” principles, why are they subject to prolonged family separations, suffering all the negative consequences of such a measure?

3- Why is it unacceptable for Brazil to insist on full payment of their salaries, as is the case of doctors from other countries, instead of via the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), through which the Cuban Government seizes 75% of their remuneration?

As the article “Havana’s Lies: How Cuba covered up the salaries of Cuban doctors in Brazil and got the PAHO involved”, published in DDC, reveals, the sending of Cuban doctors to Brazil was discussed beginning in April of 2012, but the involvement of the PAHO was not even considered until December of that year, and was adopted as a subterfuge to elude the Brazilian Congress, which would have to be consulted in the event of bilateral agreement, and also to keep from tipping the trade balance to the Cuban side, which would have happened if Brazil had paid Havana directly for the doctors contracted.

4- If the doctors are those who best know the needs of that country, why weren’t they allowed to decide for themselves whether to return or stay, and whey weren’t they consulted before making the decision, or even informed before making it public?

5- Why are those who the Government withdraws called “heroes,” but those who decide to continue offering their services in Brazil called “deserters?” And why are they barred from returning to their country for eight years?

6- If the Cuban government recognizes that the decision has an impact on the Brazilian people, how can it claim that the decision was taken in defense of the professional and human dignity of the collaborators, when they were not even consulted? This, while leaving millions of Brazilians without medical attention. What is more important: responding to an alleged attack on the doctors’ dignity, or medical attention for those in need of it?

7- The export of professional services is the country’s primary source of revenue. Medical services rank first, and the Más Medicos program is the main one, its closure meaning the loss of about 300 million dollars per year. How can “countering the offence” be preferable to renegotiating with Brazil?

8- If participation in the Program allows Cuban doctors to satisfy needs or realize aspirations impossible with the salary they receive in Cuba, and if Brazil will, in the future, open up positions for Cuban and foreign doctors, it was not difficult to deduce that many Cubans would never return, represent a considerable loss of qualified personnel on the Island. So, what is the advantage or the reason for withdrawing them, rather than negotiating?

After presenting the abovementioned questions,, Dimas Castellanos then arrives to the following conclusions:

First, in light of the fact that these medical services are exported by a State that is the doctors’ sole employer, one that prohibits them from leaving the country without permission, and forbids their relatives from accompanying them, and pays them just 25% of what they are actually earning; and that, without physical forcing them, all but obliges them to go, out of necessity, it is evident that they have no power of decision, as demonstrated by the cancellation of the Más Médicos program. The Cuban policy is one of modern slavery.

Second, the revenues of a country cannot depend strategically on sources as fragile as the contracting of professionals, nor upon subsidies distributed for reasons of ideological affinity.

Third, all of the above is closely related to the existence and defense of an economic model that, unable to produce, has forced the regime to rely on subsidies, unpaid loans, and the export of professional services under conditions of modern slavery.

Fourth, a rigorous analysis reveals the unavoidable need for deep structural reforms, including citizens’ freedoms, without which professionals will continue to be subjected to this kind of modern-day slavery, and the economy will collapse, as it is impossible to continue living on subsidies and the export of professionals’ services, a fact ignored in the new Constitution drafted by the Communist Party.